Betting against yourself

It’s not what you think will happen but what you don’t think will happen that presents the greatest opportunity in RM, writes Tom Bacon

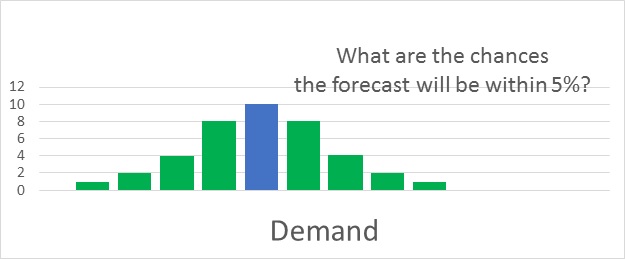

The forecast is wrong! What are the chances that your forecast will be right? Isn’t it almost a certainty that the forecast will be off a bit – potentially off a lot? Still, we construct millions of forecasts each night and then optimise inventory levels and pricing based on those, most-likely wrong, forecasts.

On top of that, we are all – us and all of our major competitors - using similar forecast methodologies. We all use similar sophisticated auto-regressive, multivariate, time of day specific, market-specific, date-specific algorithms, fundamentally based on the last three years of history, across thousands of markets. If we are under-forecasting, most probably our competitors are similarly missing the larger upside. If we are over-forecasting, most probably all of us will end up with empty seats. We are most likely collectively wrong.

Note: if the industry missed the forecast in the historic period, the model assumes the competitors will act as they did then. If everyone under-forecast demand and left empty seats, the model will tend to predict that the competition will again leave empty seats this period and will, consequently, open up our inventory too much. Everyone will become overly aggressive at the same time.

Thus, there is tremendous opportunity in expecting the unexpected, expecting our algorithms to be wrong and taking contrary action. There are two basic steps built into most RM processes that recognise the need to expect the unexpected:

1. Regular reporting on actuals across markets helps identify potential changes in demand. Focusing on variances – to the previous month to the previous year, for example – alerts analysts to a need for intervening into the model results.

2. Disciplined testing of potential changes in demand is a fundamental part of revenue management. Applying demand adjustments to a handful of markets or flights helps determine if the history-based algorithm is missing something.

In addition, however, there are a few other, bigger steps RM managers need to take:

- Devils’ advocacy. Bet against the market

Arguably, when the whole industry relies on similar history-based forecast models, the end result is for everyone to behave like lemmings – all moving to increase or decrease pricing at the same time. Thus, it is important to evaluate a contrarian view. During one aggressive industry fare sale to help stimulate demand in a weak market, one contrarian competitor held back inventory and found he alone had the seats for the higher fare demand closer to departure.

- Periodically, take a step away from models and statistics

Over-reliance on models is driving the industry consensus. A shrewd competitor moves away from models periodically and develops a more intuitive forecast based on economic and industry factors. Not “what does the (historic) model say?” but “what makes sense now?”

- Be a leader

Many RM systems have tools to prevent the ‘spiraling down’ of fares (too often, a period of low fares leads to depressed high fare demand, which in turn leads to more seats for low fares). These RM tools, however, are flight specific, occurring at a very micro level. Airlines also need to adopt a strategic orientation toward sell-up opportunities that may not be visible in the historic data.

In conclusion then, we all need to acknowledge the limitations in our forecast models and ‘expect the unexpected’. Given a convergence of industry modeling processes and too-often over-reliance on the historic model, we are very likely to miss key opportunities. There is often more revenue upside to adopting a contrarian view, and exploiting the unexpected.

Tom Bacon has been in the business for 25 years as airline veteran and now industry consultant in revenue optimisation. Questions? Email Tom or visit his website.